The Data journey or the data value chain describes the different steps in which data goes from its creation to its eventual disposal. The data journey consists of many stages. The main ones are ingestion, storage, processing, analysis, and serving. Each stage has its own set of activities and considerations.

Data ingestion is the first stage of the data lifecycle. This is where data is collected from various internal sources like databases, CRM, ERPs, legacy systems, external ones such as surveys, and third-party providers.

In this article, I will introduce the main activities of the data ingestion stage and how it is important to ensure the acquired data is accurate and up-to-date to be used effectively in subsequent stages of the cycle.

What is Data Ingestion?

Data ingestion is the process of moving data from one place to another. Data ingestion implies data movement from source systems into storage in the data journey, with ingestion as an intermediate step.

It’s worth quickly contrasting data ingestion with data integration. Whereas data ingestion is data movement from point A to B, data integration combines data from disparate sources into a new dataset. So, for example, you can use data integration to combine data from a CRM system, advertising analytics data, and web analytics to create a user profile, which is saved to your data warehouse.

Data Ingestion Activities

In this stage, raw data are extracted from one or more data sources, replicated, then ingested into a landing storage support. Next, you must consider the data characteristics you want to acquire to ensure the data ingestion stage has the right technology and processes to meet its goals. As I’ve explained in Data 101 - part 1, data has few innate characteristics. The most relevant ones for this stage: are Volume, Variety, and Velocity.

The ingestion layer can be decomposed into three sub-layers:

Ingestion Layer ©SWIRLAI.

Ingestion Layer ©SWIRLAI.

1 - Data sources

A data source system is the origin of the data used in the data journey. For example, a source system could be an IoT device, an application message queue, or a transactional database. A data engineer consumes data from a source system but doesn’t typically own or control the source system itself. As a Data Engineer/Architect, you need to understand how the data is produced and what possible options to connect it with the Data System. Also, Data Contracts will be ideally implemented here.

Here, we focus on different data sources you can ingest data. Although I will cite some common ways, remember that the universe of data ingestion practices and technologies is vast and growing daily.

- Direct Database Connection: Data can be pulled from databases for ingestion by querying and reading over a network connection. Most commonly, this connection is made using ODBC or JDBC. ODBC uses a driver hosted by a client accessing the database to translate commands issued to the standard ODBC API into commands issued to the database. The database returns query results over the wire, where the driver receives them and translates them back into a standard form to be read by the client. For ingestion, the application utilizing the ODBC driver is an ingestion tool. The ingestion tool may pull data through many small queries or a single large query. JDBC is conceptually remarkably similar to ODBC. A Java driver connects to a remote database and serves as a translation layer between the standard JDBC API and the native network interface of the target database. Although having a database API tailored to a specific programming language may seem unusual, there are compelling reasons for doing so.

- Databases and File Export: It is important for data engineers to have knowledge of how the source database systems manage file export. Exporting data involves extensive scanning that can heavily burden the database, particularly in transactional systems. Source system engineers must evaluate the most suitable time to perform these scans without adversely affecting the application’s performance. They may choose to implement strategies to mitigate the load. One option is to break the export queries into smaller segments, either by querying over key ranges or individual partitions. Another approach is to use a read replica to alleviate the load. Read replicas are particularly beneficial when data exports frequently occur throughout the day and coincide with periods of high load on the source system.

- APIs are becoming increasingly critical and popular as a source of data. Many organizations may have numerous external data sources, such as SaaS platforms or partner companies. Unfortunately, there is no standard for data exchange over APIs, which presents a challenge. Data engineers may have to invest considerable time studying documentation, communicating with external data owners, and developing and maintaining API connection code.

- Webhooks are sometimes called reverse APIs. In a traditional REST data API, the data provider shares API specifications with engineers, who then write the code for data ingestion. The code sends requests to the API and receives data in the responses. In contrast, with a webhook, the data provider defines an API request specification, but instead of receiving API calls, the data provider makes them. The data consumer is responsible for providing an API endpoint for the provider to call. In addition, the consumer must ingest each request and handle data aggregation, storage, and processing.

- Web interfaces continue to be a practical means of data access for data engineers. However, it is common for data engineers to encounter situations where not all data and functionalities in a SaaS platform are accessible through automated interfaces, such as APIs and file drops. In such cases, individuals may have to access a web interface manually, generate a report, and download a file to a local machine. However, this approach has obvious disadvantages, such as individuals forgetting to run the report or encountering technical computer issues. Therefore, it is advisable to select tools and workflows that permit automated access to data whenever feasible.

- Web scraping is an automated process for extracting data from web pages, typically by parsing the various HTML elements on the page. For example, this technique may be used to scrape e-commerce websites for product pricing data or aggregate news articles from multiple sources. As a data engineer, you may encounter web scraping in your work. However, web scraping operates in a murky area where ethical and legal boundaries may be unclear.

- Transfert appliance: When dealing with massive volumes of data (100 TB or more), transferring data over the internet can be a slow and expensive process. At this scale, the most efficient way to move data is often by physical means. Many cloud vendors offer the option to send your data via a physical device called a transfer appliance. To utilize this service, you order the transfer appliance, load your data from your servers onto the device, and then send it back to the cloud vendor, who will then upload your data into the cloud.

- Electronic Data Interchange (EDI): Data engineers often encounter electronic data interchange (EDI) as a practical reality in their work. While the term can refer to any data movement method, it typically refers to outdated means of file exchange, such as email or flash drives. Unfortunately, some data sources may only support these outdated methods due to legacy IT systems or human process limitations. Despite this, engineers can improve EDI through automation. For example, they can set up a cloud-based email server that automatically saves files onto company object storage upon reception. This triggers orchestration processes to ingest and process the data, which is more efficient and reliable than employees manually downloading and uploading files to internal systems.

- Data sharing is becoming a popular option for data consumption. Providers offer datasets to third-party subscribers either for free or at a cost. These datasets are usually shared in a read-only format, meaning they can be integrated with the subscriber’s data and other third-party datasets. Still, the subscriber does not physically possess the shared dataset. In this sense, ingestion is not considered, where the subscriber gets full ownership of the dataset. If the provider revokes access to the dataset, the subscriber will no longer have access to it.

The most important characteristic of this sub-layer is still the data velocity. In fact, data comes in two forms: bounded and unbounded. Unbounded data is data as it exists in reality, as events happen, either sporadically or continuously, ongoing and flowing. Bounded data is a convenient way of bucketing data across some boundary, such as time.

Bounded vs. Unbounded data.

Bounded vs. Unbounded data.

All data is unbounded until it’s bounded. Indeed, Business processes have long imposed artificial bounds on data by cutting discrete batches. Remember the true unboundedness of your data; streaming ingestion systems are simply a tool for preserving the unbounded nature of data so that subsequent steps in the lifecycle can also process it continuously.

2 - Data collection

Rarely will the data produced by Data Sources be pushed directly downstream. This subsystem acts as a proxy between External Sources and Data Systems. You are very likely to see one of three proxy types here:

- Collectors - applications that expose a public or private endpoint to which Data Producers can send the Events.

- CDC Connectors - applications that connect to Backend DB event logs and push selected updates against the DB to the Data System.

- Extractors - applications written by engineers that poll for changes in external systems like websites and push the Data down the stream.

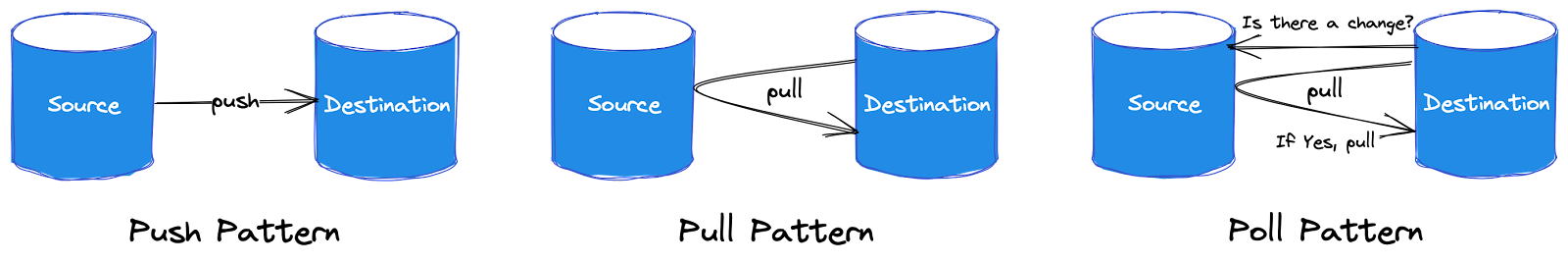

For the data collection, three patterns are relevant to consider: the Push, the Pull, and the Poll models. In the push model of data ingestion, a source system writes data out to a target, whether a database, object store or filesystem.

In the pull model, data is retrieved from the source system. The line between the push and pull paradigms can be quite blurry; data is often pushed and pulled as it works through various data pipeline stages.

Another pattern related to pulling is polling for data. Polling involves periodically checking a data source for any changes. When changes are detected, the destination pulls the data as it would in a regular pull situation.

Consider, for example, the extract, transform, load (ETL) process commonly used in batch-oriented ingestion workflows. ETL’s extract (E) part clarifies that we use a pull ingestion model. In traditional ETL, the ingestion system queries a current source table snapshot on a fixed schedule.

In another example, consider continuous CDC, achieved in a few ways. One common method triggers a message every time a row is changed in the source database. This message is pushed to a queue, where the ingestion system picks it up.

Another common CDC method uses binary logs, which record every commit to the database. The database pushes to its logs. The ingestion system reads the logs but doesn’t directly interact with the database otherwise. This adds little to no additional load to the source database.

Some versions of batch CDC use the pull pattern. For example, in timestamp-based CDC, an ingestion system queries the source database and pulls the changed rows since the previous update.

Another important data collection aspect is the source and target coupling level. With synchronous ingestion, the source, ingestion, and destination are tightly coupled with complex dependencies. Each stage of the data journey has processes directly dependent upon one another. If an upstream process fails, downstream processes cannot start. This type of synchronous workflow is common in older ETL systems, where data extracted from a source system must then be transformed before being loaded into a data warehouse. Processes downstream of ingestion can’t start until all data in the batch has been ingested. If the ingestion or transformation process fails, the entire process must be rerun.

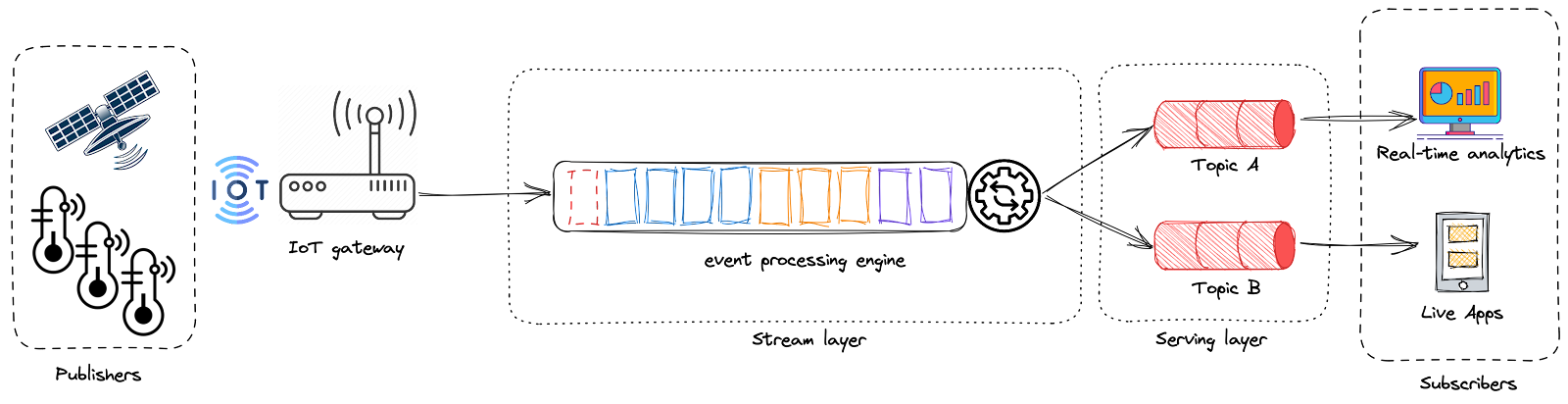

With asynchronous ingestion, dependencies can now operate at the level of individual events, as much as they would in a software backend built from microservices. Individual events become available in storage as soon as they are ingested individually. Take the example of a sensor that emits temperatures into a message queues backend (here, acting as a buffer). The stream is read by a stream processing system, which parses and enriches events (e.g., with geo-localization data) and then forwards them to a publisher/subscriber (PubSub) system that notifies subscribers when the temperature exceeds a certain threshold. None of these systems is tightly coupled to another one. If a sensor fails, the rest of the architecture remains operational to handle data coming from the other sensors.

3 - Data Movement

In most cases, you will see a Distributed Messaging system before the Data moves down the stream. Also, data validation can happen at this stage to alleviate stress from computations happening down the Data value Chain. We often interchange the terms data movement and data ingestion when discussing the velocity of data acquisition.

Moving data from source to destination involves serialization and deserialization. As a reminder, serialization means encoding the data from a source and preparing data structures for transmission and intermediate storage stages.

When ingesting data, ensure that your destination can deserialize the data it receives. We’ve seen data ingested from a source but then sitting inert and unusable in the destination because the data cannot be properly deserialized. We will talk about Serialization formats extensively in the Data Processing post.

While most ingestion tools can handle a high volume of data with a wide range of formats (structured, unstructured…), they differ in handling the data velocity. As a result, we often distinguish three main categories of data movement: batch-based, real-time or stream-based, and hybrid.

Data movement types.

Data movement types.

A. Batch-based data movement

Batch-based data movement is the process of collecting and transferring data in bulk according to scheduled intervals. The ingestion layer may collect data based on simple schedules, trigger events, or any other logical ordering. This means that data is ingested by taking a subset of data from a source system based either on a time interval or the size of accumulated data. Batch-based ingestion can be useful for companies that need to collect specific data points daily or don’t require data for real-time decision-making.

Time-interval batch ingestion is widespread in traditional business ETL for data warehousing. This pattern is often used to process data once a day, overnight during off-hours, to provide daily reporting, but other frequencies can also be used.

Time-interval vs. Size-based batch ingestion.

Time-interval vs. Size-based batch ingestion.

Size-based batch ingestion is quite common when data is moved from a streaming-based system into object storage; ultimately, you must cut the data into discrete blocks for future processing in a data lake. Some size-based ingestion systems can break data into objects based on various criteria, such as the size in bytes of the total number of events.

When implementing batch ingestion, data engineers must consider a few issues, such as snapshots vs. differential extraction, which action precedes the other transforming or loading (ETL vs. ELT), batch size, and data migration constraints…

B. Stream ingestion data movement

Real-time or Stream-based movement is essential for organizations to rapidly respond to new information in time-sensitive use cases, such as stock market trading or sensors monitoring. In addition, real-time data acquisition is vital when making rapid operational decisions or acting on fresh insights.

Publish-subscribe (PubSub) messaging systems are relevant here, allowing real-time applications to communicate their data by publishing messages. Receivers are subscribers of these systems and receive data as soon as it is published by the data source. These kinds of tools should be highly scalable and fault-tolerant to handle high volumes of data.

When implementing stream ingestion, data engineers must consider a few issues such as schema evolution, late-arriving data, out-of-order data, data replay, time to live (TTL), message size, and failure handling (e.g., Dead-Letter queues)…

C. Hybrid ingestion data movement

Hybrid data movement is an incremental setup that consists of both batch and stream methods. It performs a delta function between the target and the source(s) and assesses missing information. Initially, there is no data in the target. Thus, the hybrid ingestion tool extracts a snapshot of the data sources and transfers it to the landing zone as a batch. Once the initial load is done, it ingests further data as a stream.

One of the most used tools in this category is the Change Data Capture (CDC). The CDC constantly monitors the database transaction logs or redo logs and moves changed data as a stream without interfering with the database workload.

Data Ingestion’s Underlying Activities

Data engineering has evolved beyond tools and technology and now includes a variety of practices and methodologies aimed at optimizing the entire data journey, such as data management and cost optimization, and newer practices like DataOps.

These undercurrent activities are important for ensuring data ingestion is done effectively and efficiently. By managing data effectively, optimizing costs, and adopting best practices like DataOps, data engineers can ensure that the data they ingest is accurate, reliable, and available to those who need it when they need it.

-

Security: Moving data introduces security vulnerabilities because you have to transfer data between locations. The last thing you want is to capture or compromise the data while moving. Consider where the data lives and where it is going. Data that needs to move within your VPC should use secure endpoints and never leave the confines of the VPC.

-

Cost optimization: consider additional costs for data transfer from source to target. These costs can quickly become a blocker for any data initiative. Like security, data movement is critical, and its cost should be analyzed and assessed before deciding which ingestion tools and technologies you choose.

-

Data Management is an essential aspect of the data journey, and it starts right from the data ingestion stage. Data engineers must be mindful of various aspects of data management, including data lineage, cataloging, schema changes, ethics, privacy, and compliance while ingesting data. This ensures that the data is well-organized, easily accessible, and complies with regulatory requirements. In addition, by implementing effective data management practices, data engineers can ensure that data is available for analysis and decision-making, supporting business objectives.

-

DataOps: Monitoring is essential in ensuring the reliability of data pipelines. Proper monitoring allows for detecting pipeline issues and failures as they occur, enabling timely resolution and preventing downstream dependencies from being affected. Additionally, monitoring can help identify areas for improvement and optimization, leading to more reliable data pipelines overall. In the ingestion stage, monitoring is especially critical because any issues or failures can cause a ripple effect throughout the rest of the data journey.

-

Data Quality: Data Observability is important to realize data quality and build stakeholder trust. It provides an ongoing view of data and data processes. However, having insights about the reliability of your pipelines is not sufficient. You must consider establishing a data contract with SLA with upstream providers. An SLA provides expectations of what you can expect from the source systems you rely upon. I’ll refer to James Denmore’s definition of data contracts: “A data contract is a written agreement between the owner of a source system and the team ingesting data from that system for use in a data pipeline. The contract should state what data is being extracted, via what method (full, incremental), how often, and who (person, team) are the contacts for both the source system and the ingestion. Data contracts should be stored in a well-known and easy-to-find location such as a GitHub repo or internal documentation site. If possible, format data contracts in a standardized form so they can be integrated into the development process or queried programmatically.”

-

Orchestration: As the complexity of data pipelines increases, a robust orchestration system becomes essential. In this context, true orchestration refers to a system that can schedule entire task graphs rather than individual tasks. With such a system, each ingestion task can be initiated at the appropriate scheduled time, and downstream processing and transformation steps can start as ingestion tasks are completed. This leads to a cascading effect where processing steps trigger additional downstream processing steps.

Summary

The article discusses the importance of data ingestion in the data journey lifecycle. The article highlights the various challenges that data engineers may face during data ingestion, such as data velocity, data quality, data access, and source disparity. It also discusses the various sub-layers for the ingestion and how to choose the right tools and technologies to ensure efficient data ingestion.

It also emphasizes the importance of properly monitoring and putting in place data contracts to ensure data reliability, better data quality, and effective incident response. Finally, it discusses the role of data management in data ingestion, including data cataloging, schema changes, and compliance with ethics and privacy regulations.

References

- James Denmore, Data Pipelines Pocket Reference: Moving and Processing Data for Analytics (O’Reilly 2021).

- Reis, J. and Housley, M. Fundamentals of data engineering: Plan and build robust data systems. O’Reilly Media (2022).

- “Decomposing the Data System”, Aurimas Griciūnas (SwirlAI).